Kyoto: The New Cultural Capital

In 794, Emperor Kanmu relocated the capital to Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto), marking the beginning of a new era. Unlike Nara, which was heavily influenced by Chinese models, Kyoto developed a uniquely Japanese style of governance and culture. The city’s layout, inspired by Chinese geomancy, was designed to reflect harmony and balance.

Kyoto quickly became the center of aristocratic life, where court nobles engaged in poetry contests, seasonal festivals, and elaborate rituals. The emphasis was not on military power, but on elegance, subtlety, and emotional sensitivity.

The Tale of Genji and Courtly Life

Written by Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting at the imperial court, The Tale of Genji is often called the world’s first novel. It offers a vivid portrayal of Heian court life—its romances, politics, and aesthetic values. The novel’s themes of impermanence (mujō) and refined beauty (miyabi) reflect the philosophical depth of the time.

Visitors to Kyoto can explore this world through:

Religion and Aesthetics

While Buddhism remained influential, the Heian period saw the rise of esoteric sects like Tendai and Shingon, which emphasized ritual, mandalas, and mystical practices. These schools blended spiritual depth with artistic expression, contributing to the era’s rich visual culture.

Art & Faith: The Evolution of Buddhist Sculpture in the Heian Period

The Heian period witnessed a remarkable transformation in Buddhist art, especially in sculpture. Moving away from the rigid, symmetrical styles of earlier periods, Heian-era statues began to emphasize softness, grace, and emotional depth.

Sculptors like Jōchō, a master of the yosegi zukuri (joined wood-block) technique, created serene and compassionate figures that reflected the Pure Land Buddhist ideals of salvation and inner peace. His most famous work, the Amida Buddha at Byōdō-in Temple in Uji, remains a masterpiece of Japanese religious art.

These sculptures were not just devotional objects—they were expressions of aesthetic philosophy. The gentle curves, calm expressions, and harmonious proportions embodied the Heian court’s pursuit of refined beauty and spiritual elegance.

From Characters to Culture: The Birth of Hiragana and Katakana

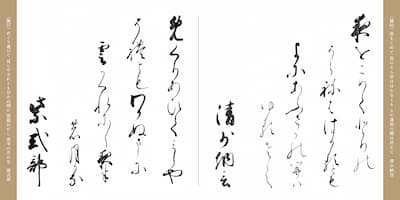

One of the most culturally significant developments of the Heian period was the creation of hiragana and katakana, Japan’s native syllabaries. Derived from Chinese characters (kanji), these simplified scripts allowed for more fluid and expressive writing.

Hiragana, often called onnade (“women’s hand”), was used primarily by court women for personal letters, poetry, and literature—including The Tale of Genji. Its flowing style suited the emotional and aesthetic tone of Heian prose.

Katakana, on the other hand, was developed by Buddhist monks as a shorthand for reading and annotating Chinese texts. Its angular form made it ideal for scholarly and religious use.

Together, these scripts marked a turning point in Japanese identity. They enabled the creation of a uniquely Japanese literary voice, independent from Chinese influence, and laid the foundation for the rich linguistic culture that continues today.

Takeaway

The Heian period was a time of cultural blossoming, where elegance, emotion, and spiritual depth defined the aristocratic worldview. From literature and religious art to the birth of Japan’s native writing systems, this era laid the foundation for a distinctly Japanese identity. While Kyoto became the new capital, it’s important to note that the current Kyoto Imperial Palace is not the original Heian-era palace, but a later reconstruction. Here are the key insights from this episode:

Key Points:

- The capital moved from Nara to Kyoto, initiating a shift toward native cultural development.

- Aristocratic life emphasized poetry, seasonal rituals, and refined emotional expression.

- The Tale of Genji, written by Murasaki Shikibu, reflects the aesthetic and philosophical values of the time.

- Hiragana and katakana emerged from Chinese characters, enabling a uniquely Japanese literary voice.

- Buddhist sculpture evolved toward emotional realism, with masterpieces like Jōchō’s Amida Buddha at Byōdō-in.

- Esoteric Buddhist sects such as Tendai and Shingon influenced both spiritual practice and artistic expression.

- The current Kyoto Imperial Palace is a later reconstruction and differs from the original Heian palace.

FAQ

Is the current Kyoto Imperial Palace the same as the one from the Heian period?

No. The original Heian palace (Heian-kyū) was located elsewhere and was lost to fire in the 13th century. The current Kyoto Imperial Palace was rebuilt in the 19th century and reflects later architectural styles, though it was inspired by classical designs.

What role did Buddhism play in Heian-era art?

Buddhism deeply influenced Heian aesthetics, especially in sculpture. Artists like Jōchō pioneered techniques that emphasized emotional serenity and spiritual elegance, as seen in the Amida Buddha at Byōdō-in Temple.

How did hiragana and katakana originate?

Both scripts evolved from Chinese characters. Hiragana was used mainly by court women for literature and poetry, while katakana was developed by monks for scholarly annotation. Together, they enabled a uniquely Japanese literary culture.

Can I see Heian-era cultural sites in Kyoto today?

Yes! While the original palace no longer exists, places like Byōdō-in Temple, Heian Shrine, and the Kyoto Imperial Palace offer insights into the aesthetics and spiritual life of the Heian period.

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)